Town of Galway School House No. 5, built circa 1850. Image Courtesy of the Galway Public Library

On summer days when I was my children’s age, I spent a lot of time outside in the yard of our rural New York home.

It was not unusual for cars to drive by our house slowly. The driver or the passenger, who looked to be as old as my grandparents did then, would gesture at our small home, the giant maple and beech trees or the farm fields beyond.

My parents hadn’t lived there long before they struck up conversations with some of these folks, who may have been strangers to us, but not to our house.

We lived in what was once the one-room school house for School District No. 5 in the town of Galway, New York. Additions were added over the years, including by my parents. But the original, rectangular structure of the school house can still clearly be seen.

The retirees who would sometimes stop and look at the house were former students. The school house went out of use by the 1940s, as rural districts began to centralize. One of the stories we sometimes heard from the former students was that they had buried time capsules in mason jars beneath trees they planted for Arbor Day.

My hometown established 12 school districts in 1812 and it isn’t exactly clear when School House No. 5 was built, but we think sometime in the 1850s or earlier. It was around then that public education in rural America – which was where most Americans lived until the early 1900s – took the form it would have for much of the next century. Civic participation played a key role.

A Young Yorkers Leaflet published in 2009 by the New York State Historical Association is a great resource for teachers and the general public. It is set up in a lesson plan format, which includes suggested learning activities.

It describes what one-room school house were like in the 1840s and notes they were the standard mode of education for rural America into the early 20th Century.

Here are some interesting facts about schools in the 1840s:

- A system of state aid to establish schools in New York was started in 1795. This system enrolled nearly 60,000 students in 1,300 schools before the aid system collapsed in 1800.

- Proceeds from state land sales helped boost the system in the early 1800s under the Common School Fund. In 1814, a system of funding that included state aid, local taxes and rate bills, which were a form of tuition, kept schools open. However, by the 1830s, the schools were underfunded and often in poor condition.

- The 1840s saw a renewed interest in public schools and school trustees – elected by town voters – supervised the schools. Common schools had 557,229 students ranging in age from 5 to 21 at 10,127 schools in the state. The school year averaged 8 months, with a winter term and a summer term. Rate bills eventually disappeared by 1867, making state aid and local taxes the sole source of funding for the public schools.

- Schools were typically one teacher, with often a male in the winter term to help keep charge of a larger number of older boys and a female in the summer term, when attendance was limited to women and younger boys. Teachers usually had an eighth grade education and had attended a two-week teacher training program. Women made up to $7.50 a month, while men often earned double that. Contracts were negotiated with the school trustees, which were the equivalent of today’s school board members.

- There were no grade levels or promotions and students were often grouped according to reading and spelling levels. School days had afternoon and morning sessions with a 1 ½ to 2-hour recess for lunch. They began with a Bible reading and moral lessons were a part of the curriculum. Math problems and reading recitals were the focus for older children, while young students learned to read and write and do simple arithmetic. Students also learned history and geography.

- Student equipment included goose-quill or steel-nibbed pens, slates and slated pencils and rulers. Classrooms kept ink supplies, had blackboards, a stove for heating in the winter and warming up food, water buckets, and, of course, books.

- Student lunches would typically include bread and butter, cheese, beans, potatoes, and fruit when it was in season. At recess children played hide-and-seek, snap-the-whip and London Bridge. Boys often whittled with jackknives.

- ‘Spare the rod and spoil the child.’ Discipline and order were the rule of the day, and corporal punishment was accepted.

Today’s public education system may not look anything like it did in 1840, but its roots are still the same. On May 21, voters across New York state will head to the polls to approve budgets and vote for board of education members.

At one time, this vote was held as part of the annual school district meeting, which is still a legal term for the vote date, although it has long since ceased to be an actual meeting.

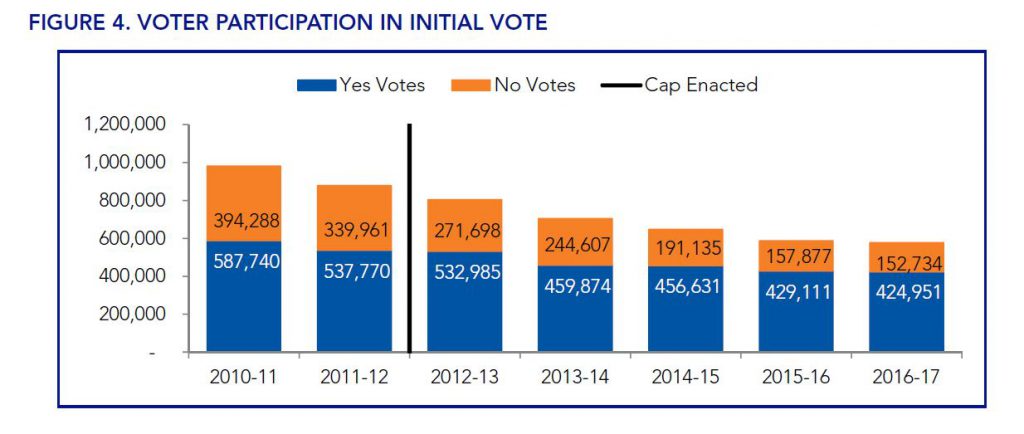

But in recent years, there have been significant changes in the number of school district residents who are participating in the school budget vote, or annual meeting. Last year, data from the New York State Association of School Business Officials showed the number of votes cast statewide in school budget votes has dropped by about 41 percent since 2010. At the same time, the total number of ‘yes’ votes increased from about 60 percent of the total votes in 2010 about 74 percent.

What does this all mean for parents? Does lower voter turnout mean trouble down the road for school districts?

Michael Borges is the executive director of NYSASBO, and he confirmed what many others have said about voter participation in school budget votes: The property tax levy limit law, which is now in its sixth year, has had a chilling effect on voter participation.

Because school districts are now restricted by how much they can raise their tax levy limit with a simple majority vote, one of the motivating factors – fear of high tax increases – has diminished for many district residents. School districts who seek to override the tax levy limit, or cap, to preserve programming must get a supermajority approval from voters.

There has also been a general trend in New York State of lower voter turnout at all levels, including last year’s presidential election, when the state ranked 41st in voter turnout. It was even worse in 2014 during the Congressional midterm and gubernatorial election in New York when the state ranked 49th in voter turnout.

Source: NYSASBO

Borges said it isn’t clear exactly what the long– term ramifications are for lower voter turnout for school budget votes.

“Sometimes a ‘no’ vote prompts a large turnout by the ‘yes’ vote,” Borges said.

But a larger issue may simply be about civic responsibility.

“You shouldn’t take the right to vote for granted,” Borges said.

Voting on school budgets may also be a lesson in and of itself.

“You can serve as a role model for your children,” Borges added.

With declining voter turnout and many issues related to local control of school districts being debated, it perhaps isn’t surprising that some are questioning why we even have school budget votes today .

Borges said New York is a bit of an anomaly in this regard.

“We are one of the few states in the country that actually vote directly on school budgets,” Borges said.

Other levels of government in New York State, including towns, cities, counties and the state itself, rely on elected representatives to adopt their respective budgets.

Buried treasure

About a month ago, my children and I were metal detecting at School House No. 5 looking for the long lost time capsules in the mason jars. We never found them, but we did find an 1867 shield nickel, a few buttons from the early 1800s and a 1924 class ring. To my kids, this was buried treasure.

Maybe someday, a metal detectorist will be out with his or her children at the former site of one of our sprawling “modern” school buildings and dig up an iPhone. It’s nice to think that on that future day, the detectorist, with his or her kids in tow, will dutifully line up to cast a ballot in a school budget vote, but I guess time will tell.

Jake Palmateer is a public information specialist for Capital Region BOCES. He is the father of a 7-year-old son and a 9-year-old daughter. Their adventures include camping, hiking, metal detecting, painting, stargazing, reading, fishing, soccer, mowing the lawn and baking cupcakes.

Skip to Content

Skip to Content Capital Region BOCES

Capital Region BOCES